Being new to options, there’s a lot of industry jargon thrown your way — spreads, slippage, margins, etc.

It can get confusing, I know.

When I first began trading options, I also struggled to decipher what felt like Morse code.

But… I have TEACHER running through my veins, and I’m here to hold your hand through all of it.

Because to be the most successful options trader possible, you must first find an experienced trader who is willing to show you the ropes and simplify things.

I would be honored if that mentor were me.

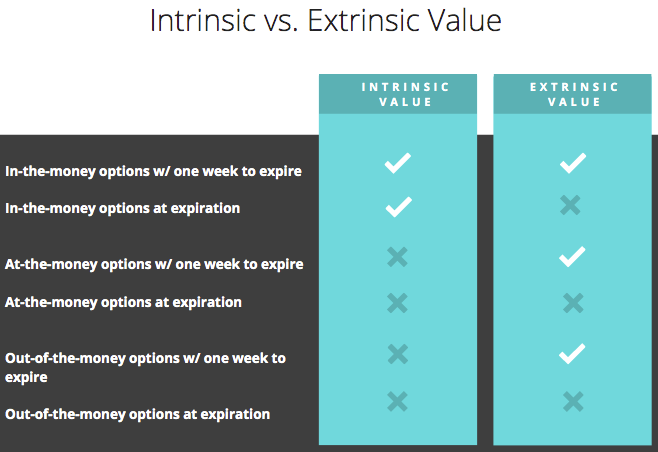

That said, two of the most important terms we throw out a lot are intrinsic value and extrinsic value.

These two factors make up an option’s price.

And one of them is CRUCIAL to option sellers like me.

How Are Option Prices Determined?

An option’s value is broken up in two ways: intrinsic value and extrinsic value.

Intrinsic value is the easiest to determine. It’s the difference between the stock price and the strike price, assuming the option is in the money (ITM).

- A call option is ITM when the stock is trading above the strike price.

- A put option is ITM when the stock is trading below the strike price.

Extrinsic value is mostly comprised of time value. The longer an option has until expiration, the more time value it has (meaning it’s more expensive).

Implied volatility (IV) — how much volatility the options market expects for the shares — also factors into extrinsic value.

All options — ITM, at-the-money (ATM), and out-of-the-money (OTM) — can have extrinsic value.

- An option is ATM when the strike is around the stock price.

- A call option is OTM when the stock is trading below the strike price.

- A put is OTM when the stock is trading above the strike price.

When the option expires, it is worth ONLY its remaining intrinsic value.

A Real-Life Example

So, for instance, Apple supplier Skyworks Solutions (SWKS) made noise yesterday after an upgrade to “buy” from “underperform” at BofA-Merrill Lynch.

The stock was up 2.7 points to trade just over $104.

Now, let’s take a look at the options chain for SWKS calls.

The stock’s 102-strike calls are ITM, because $102 (the strike) is below $104, right?

That means all the 102-strike calls have $2 in intrinsic value ($104 – $102).

But you’ll notice the weekly 12/13 102-strike calls — which expire this Friday — are asked at $2.90. So they hold 90 cents in extrinsic value ($2.90 – $2 in intrinsic value).

The weekly 12/20 102-strike calls — which expire next Friday, Dec. 20 — are asked at $3.50. That means they hold $1.50 in extrinsic value ($3.50 – [$104 – $102]).

They cost more because there’s more time for the stock to make a big move.

Meanwhile, the 106-strike calls have NO intrinsic value. That’s because SWKS shares aren’t trading above $106.

The weekly 12/13 106-strike calls are asked at 75 cents — that’s all extrinsic value.

The same calls in the 12/20 series are asked at $1.35, because again, they have another week of life, and thus are more expensive.

Time Decay is an Option Seller’s Friend

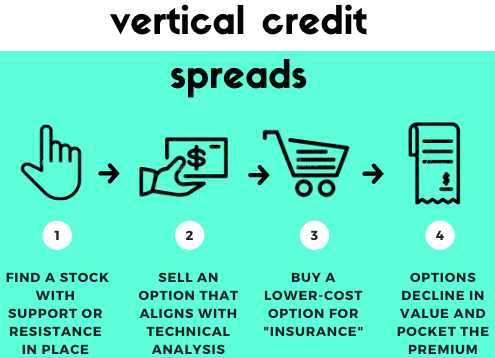

I trade vertical credit spreads in Weekly Windfalls. That means I sell an option at a strike I think will act as support (a put) or resistance (a call).

I then buy “options insurance,” purchasing an OTM put or call to limit losses in the event the stock moves against me.

So, a vertical spread consists of two options: one sold, one bought.

Because I receive more money for the option I sold than the option I bought, my spread is established for a net credit, as opposed to a net debit. Therefore, even though I also buy an option, I consider myself a seller.

In the ideal vertical credit spread situation, both options will expire worthlessly. (Now, that doesn’t often happen — you don’t have to wait until expiration day to take profits.)

In other words, I don’t want the options to finish ITM and have intrinsic value.

As with anything you sell — clothes, options, your immortal soul — you want to get as much money as you can, right?

Therefore, my goal is to capture as much premium as I can when I initiate the spread, and then let time decay erode the value of the options, so I can pocket as much as possible.

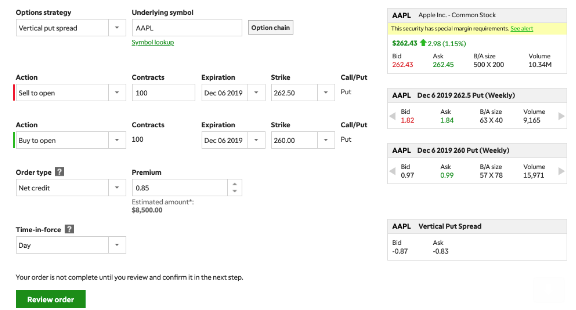

How I Made $6,500 on AAPL By Eroding Extrinsic Value

Last week, for instance, I was bullish on Apple (AAPL), which was trading around $262.50.

I sold weekly 12/6 262.50-strike puts for about $1.82 each. Since the puts were ATM, that premium consisted of mostly extrinsic value.

I then bought 12/6 260-strike puts for about 97 cents each — again, that’s all extrinsic value, since AAPL was trading above $260.

The spread was opened for a net credit of 85 cents per pair of puts, or $8,500 total (since each option controls 100 shares, and I put on 100 spreads).

That’s the MOST I could’ve made on the trade, had AAPL ended above both strikes by the close on Friday, Dec. 6, when the options expired.

The NEXT DAY — on Thursday, Dec. 5 — time decay had eroded the value of the options, which still weren’t in the money, and I banked $6,500 on the trade!

In fact, last week was a NEARLY PERFECT week for my premium Weekly Windfalls subscribers.

0 Comments